Statement for the show:

I hadn’t painted in fifteen years when, in 2005, I saw The Poetry Center’s "Poetry and its Arts: Bay Area interactions 1954 – 2004.” Not only is it located just two flights upstairs from my office in the Humanities building at SFSU, but also it has been the touchstone of a poetics from which my own derive, a kind of Neo-Projectivist/Surrealist idea of the imagination. The Poetry Center is home to me and the show featured visual works of many poets I admire. I had already had the notion that I wanted to begin some sort of visual work but the show was the final straw and I began to paint, with a somewhat-obsessive drive, about two summers ago.

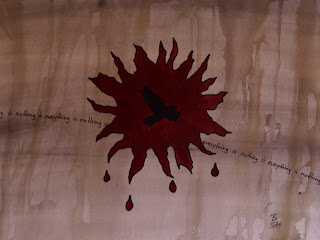

I’ve always been interested in art that is guided by forces larger than itself, art that follows more than hammers the contours of thought, whether linguistic, visual or otherwise. And “nature” is the word we give to the largest context, the most permeating materiality, the system of interrelated forces so complex, so enormous and so minute, so internal and external, that it extends far beyond the limitations of imagination and is, therefore, marvelous. This is Whitman’s “spear of summer grass.” But in an ecosystem poised at the brink of collapse, a world of drowning polar bears, disappearing bees, dying coral reefs and increasingly-intense weather events that kill tens of thousands of human beings at a time, our understanding of this system of systems is tinged with peril and fragility. As Robert Duncan says,

So does she arouse in us apocalypse

and in Nature the Furies stir.

“She” in this poem “Where the Fox of This Stench Sulks” is “my beloved Nation” gone missing, a nation that has lost its way. We all understand that the interaction of the political/social and the natural world is at the root of most environmental problems today; humanity’s impact alone, primarily that of industrialized societies, has put the earth’s environment in a dangerous state. And the relationship between the human and natural has been ingrained in our psyches for centuries as an adversarial one. But while each of us leaves footprints on the ecosystem, we always exist WITHIN it. After all, who is not a part of nature? We are all part of what Gary Snyder has called “one vast breathing body.”

There can be no doubt that nature, the context for our existence--as, for example, symbolized by the birds in Alfred Hitchcock’s film--not only cannot be controlled, but (if anthropomorphized) is pissed off. And there can be no doubt that it will have its way with our desires. But I find comfort in Duncan’s belief that

Phases of meaning in the soul may be like phases of the moon, and, though rationalists may contend against the imagination, all men [sic] may be one, for they have their source out of the same earth, mothered in one ocean and fathered in the light and heat of one sun that is not tranquil but rages between its energy that is a disorder seeking higher intensities and its fate or dream of perfection that is an order where all light, heat, being, movement, meaning and form, are consumed toward the cold.

Imagination is a deep connection with commonality, with the “one ocean” and “one sun.” We must learn to read natural systems more accurately, to listen with imagination to their direction.

❖

These paintings represent an attempt to be guided visually and artistically by the imagination’s interaction with natural forms. Poetry is encoded within the forms of the world—one only has to look closely to see it. I have found that, once embedded in the paintings, the words to my own poems become something other than what I intended, as they are fragmented and redistributed. And the reader of the paintings has a much different experience than what I may have intended. The image guides.

I’ve also been guided artistically by a number of other forces—first and foremost, the flora and fauna of East Oakland (There’s more “there there” than you might think), the landscape paintings of Egon Schiele, the flora of the McIntyre Creek area of the Sequoia National Monument and the recent exhibit of Tonalist painters Arthur and Lucia Mathews at The Oakland Museum of California. Also, Basil King’s kind words of guidance have been very helpful.

Words of encouragement from friends have been incredibly important as well, especially (but not limited to) Steve Dickison who used images of my paintings on the Poetry Center calendar and website; my co-editors of 26, especially Elizabeth Robinson who suggested the use of my artwork for the cover of issue E; Susanne Dyckman who encouraged me to show my work at a backyard reading at her house last summer; Avery Burns (also co-editor of 26) who invited me to do this show and Andrew Joron and Rose Vekony who encouraged me to pursue my initial tenuous ideas. Finally I reserve special thanks for meu amor, Elisa, who is both my harshest critic and staunchest supporter.

Everything is nothing is everything,

Brian